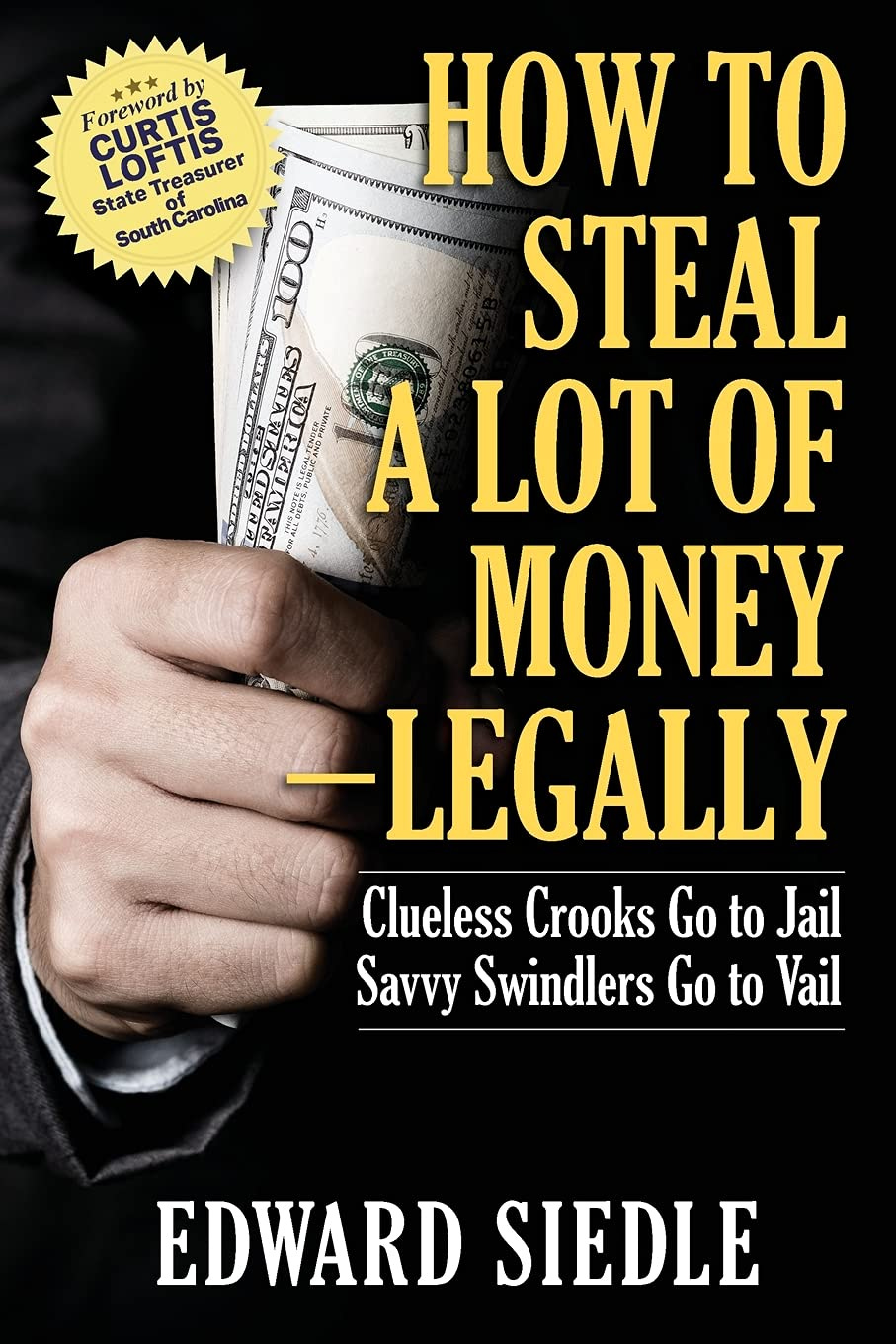

Teaching Forbes Readers How To Steal A Lot of Money--Legally

What began as a series of articles on the fine art of stealing (legally) became a bestselling book over a decade later.

In 2012, I decided to take a break from railing about Wall Street thievery and write a short series of brutally truthful articles for Forbes.com celebrating—as opposed to bemoaning—the inescapable conclusion that intelligent financial criminals often do very well indeed. It was time to openly embrace shining reality, as opposed to continue to curse the darkness, I reckoned.

In March of that year, I wrote the first in what would become a series of articles for Forbes entitled, How to Steal a Lot of Money. I wasn’t sure how popular the series would be or how long it would run but I figured I’d write about the subject in installments whenever time permitted.

One of the weird things about forensic work is that there can be long periods of downtime, when seemingly not a single client in the whole wide world wants an investigation into their millions or billions or even trillions of dollars in jeopardy. One month you can be on a roll—a minor celebrity appearing at press conferences, on talk radio, and television; the next month you’re left feeling like an under-employed nobody.

The brilliant fictional detective Sherlock Holmes, who was not a regular drug addict, resorted to cocaine and morphine during periods when he was idle—having no case at hand—in protest against mental stagnation.

I’m no drug-crazed Sherlock. In order to be an effective investigator, I have to control both my enthusiasm—(i.e., question my strongest instincts or hunches until all the facts come in), as well my discouragement—(i.e., be mindful that positive outcomes I have not envisioned may emerge from the wreckage). Dramatic mood swings need to be held in check to survive the rollercoaster ride of forensic investigations.

Downtime can be maddening for the over-active mind and is precisely when one is most likely to do something stupid out of desperation. The “How to Steal” series would, I figured, keep me out of harm’s way—at least free from self-inflicted harm.

The first article began with the following provocative statements:

“It’s been said that crime does not pay and that cheaters never prosper. Neither of these statements is true and you should not be dissuaded from a life of theft by such homilies.”

With those words, I began to teach legal thievery.

How to Steal a Lot of Money: Part I in a Series

Forbes, March 2, 2012

It’s been said that crime does not pay and that cheaters never prosper. Neither of these statements is true and you should not be dissuaded from a life of theft by such homilies. History is replete with examples of people who have done very well for themselves by stealing from others. Vast personal fortunes have been amassed using illegal, ahem, business practices. Call them “robber barons” or aggressive capitalists, many were criminals. Furthermore, since financial crimes involving the greatest sums of money are rarely reported (for reasons we’ll get to later), crime pays far better than historical accounts would suggest.

To be successful, a thief must plan his crimes carefully, weighing potential risks against rewards. In his classic book, The Intelligent Investor, Benjamin Graham, proposed that risk averse investors seek a margin of safety, or leave room for error, to protect themselves from both poor decisions and market downturns. If you’re aiming to get involved in financial crimes involving millions or billions, best you acquaint yourself with such investment concepts and incorporate them into your planning. (Warren Buffet is a big fan of Graham's. You might want to learn about him too.) Idiots, who rob banks using brute force, at best bolt with a few thousand dollars. These saps almost always get caught and sent to prison for a long time. Hopefully, high risk, low reward ventures are not appealing to you. If they are, read no further. Intelligent thieves get their hands on buckets of other people’s money without the use of force and prey upon victims that will almost certainly not report the criminal taking. Does that sound too good to be true? It’s not but there is an art to crafting the perfect crime.

The first part of the above equation, getting victims to willingly part with their money is relatively easy. Financial advisors, bankers, brokers, realtors, and a host of other professionals are in businesses that involve getting people to hand over their hard-earned money for seemingly legitimate financial purposes, including the good, the bad, and the ugly. (Don't be intimidated—many of these professions do not require even a high school diploma.) Remember that outrageously bad investment schemes that are doomed to fail the investor and are guaranteed to reward only the scammer (promoter) are generally not illegal. Ask anyone on Wall Street.

If you can come up with a far-fetched idea that transfers the investor’s wealth to you dollar-for-dollar, legally, you’ll never go hungry.

My advice: Don't grab all the money at once, slowly bleed the accounts. It's far safer to skim 10% annually than grab 100% all at once. The former is Wall Street and the latter, Madoff.

I recommend that you seek out lawyers experienced in planning scams for Wall Street clients to assist you in structuring your enterprise and creating selling materials that tell the awful truth—albeit in words no investor could possibly understand. Ask around for a legal beagle with experience in structured notes, hedge fund of funds, or variable annuities. These guys should have the exact skills you’re looking for, including an utter lack of conscience. To keep investors in the dark as much as possible, consider making the prospectus or offering documents difficult (but not impossible—that’s going to far) to obtain. Use past and future projected financial performance numbers and “invest” client monies in junk that’s really hard to value. Remember, you don’t have to lie to get people to invest in a bogus scheme. As much as possible, try to tell the truth in a way that doesn’t kill the sale. Truth may be one of your “get out of jail free” cards.

Here’s another strategy that may keep you out of the hoosegow: Schemes that, if push comes to shove permit you to return the investor’s principal years later (with you keeping all the interest and related gains) almost never are prosecuted. Regulators and law enforcement, lacking investment savvy, reckon that if the investor gets back the money he invested, he’s not been harmed. Let the ignorance of others always be an opportunity for you. If you keep just enough money on hand to return principal to investors (that margin of safety we talked about earlier) you should be free to use, perhaps invest, and enjoy other people’s money for years. If you can successfully use other people's millions to make you millions, what do you care if you have to give them back their original investment someday or pay a nominal fine? On Wall Street it is said that pigs get fat but hogs get slaughtered. Don't be a greedy hog.

While a good con man can amass a tidy fortune, there is that pesky problem of widows and other sympathetic victims who complain. Their pleas for justice can make your life a living hell and, of course, you may have to give them some of their money back. Aim higher: this does not have to be your fate.

The best possible victims are those who will never report the crime or go after you for their money. These saps would rather keep the loss private or pass it onto their insurers who will pay it without asking questions. Believe it or not, insurers regularly decide to pay off claims related to significant financial crimes without pursuing the wrongdoers. Just make sure you’re the type of wrongdoer they don’t want to go after.

In the next installment of this series, I’ll discuss finding the perfect victim using proven techniques. Until then, steal smartly!

After reading the first article of the series in Forbes, an individual—who I’ll call Duncan—contacted me with some questions.

“Mr. Siedle, your How to Steal a Lot of Money article was fascinating, not to mention very entertaining. Is another article in the series coming out soon? If not, why not? Learning about how Wall Street wheels and deals is very interesting to me. The public deserves to learn about the industry practices that undermine their financial security and, as far as I can tell, you’re the only one writing about scamming at the highest levels.”

I replied to Duncan thanking him for his comment and assured him I was busily working on the next article in the series.

I lied.

In fact, I was so disappointed in the reader response to the first article that I was considering dropping the idea of a series. Screw it—it was a waste of time, I figured.

There’s more to the story coming soon...

To purchase the book click here.