Alaska Workers Hoodwinked Out of State Pension Must Be Protected

Testimony of Edward Siedle before Alaska Senate Labor & Commerce Committee

As a result of an article I wrote in Forbes last week, I was invited to testify yesterday before the Alaska Senate Labor & Commerce Committe on behalf of state workers who were forced to unwittingly sacrifice their pension benefits 17 years ago. Here’s what I had to say:

“Good afternoon Chair Bjorkman and the members of the Alaska Senate Labor & Commerce Committee. For the record, my name is Edward Siedle, and I am a financial expert in the area of pension systems. I am testifying before you from Boca Raton, Florida. My short bio has been provided for you at your desks. If there are no questions, I will proceed with my testimony?”

I have been referred to by media as "the Sam Spade of Money Management," "the Pension Detective" and "the Equalizer" for my pioneering work investigating money management abuses.

I am the nation’s leading expert in forensic investigations of retirement plans. A former U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission lawyer and industry executive with over 40 years of experience, I have investigated well over $1 trillion in retirement plans.

In 2016, I won the first whistleblower award from the State of Indiana; in 2018, I received the largest Commodity Futures Trading Commission whistleblower award in history―$30 million. And in 2019, I won the largest whistleblower award from Securities and Exchange Commission in the amount of $48 million. I was named as one of the 40 most influential people in the U.S. pension debate by Institutional Investor magazine for 2014 and 2015.

In 2020, I and Rich Dad, Poor Dad bestselling author Robert Kiyosaki, co-authored the book, Who Stole My Pension? How You Can Stop the Looting.

Most recently, I wrote How to Steal a Lot of Money—Legally, which offers an engaging, novel approach to teaching financial literacy.

Millions have read of my investigations in articles in Forbes. In addition to television interviews on CNBC, Wall Street Week, and Bloomberg News, I recently appeared in two full-length documentary films, The Baby Boomer Dilemma and The Paradigm of Money. A member of the Florida bar, I am currently representing Screen Actors Guild members in a class action lawsuit regarding changes to the healthcare plan during the Covid pandemic. Ed Asner, known fondly to most Americans as Lou Grant, was the lead plaintiff in the ongoing case before his passing.

I’d like to begin by tell you a personal story about how I began my forensic work, which, I believe, explains both my commitment to protecting workers retirement savings and my final recommendations to you today.

The year The Beatles released the love song, When I’m 64 I was a teenager already thinking about aging, elder care and retirement.

A teenager thinking about getting old may seem unlikely.

Let me explain.

I spent my teenage years in Uganda, East Africa with my father until one day in July, 1971 he failed to return from a journey—a safari, as we’d say in Swahili—to a remote part of the country.

He and I had celebrated my 17th birthday a few days before he disappeared.

My father was an American doctor of gerontology teaching at Uganda’s Makerere University and conducting field research into care of the aged—the elderly—in African traditional societies.

Why did he choose to study how Africans took care of their elderly?

Because in the mid-1960s, my father had vision and realized that America’s population demographics—the massive Baby Boom generation—meant that in the decades to come, as 80 million hippies got older, our nation would have to care for them.

For the first time in history, this young nation—a nation which celebrated youth—would have to deal with an invasion of elders.

And America, he knew, was not prepared.

You could say he foresaw the American elder care and retirement crisis we are struggling with today.

Perhaps how African societies traditionally cared for their elders might provide answers, he thought.

My father traveled extensively throughout remote parts of Uganda—which we used to call “the bush”—meeting with missionaries and others caring for the elderly who could not care for themselves. Through his research and travels he had developed a wide network of reliable contacts who kept him informed as to happenings in the bush.

Unbeknownst to me and his colleagues at the university, the intelligence he gathered was also shared with American intelligence agencies.

In 1971, when he disappeared in the garrison town of Mbarara, he was investigating rumors that Idi Amin, the new President of Uganda, had butchered hundreds of his own army soldiers stationed at the garrison—without firing a single bullet.

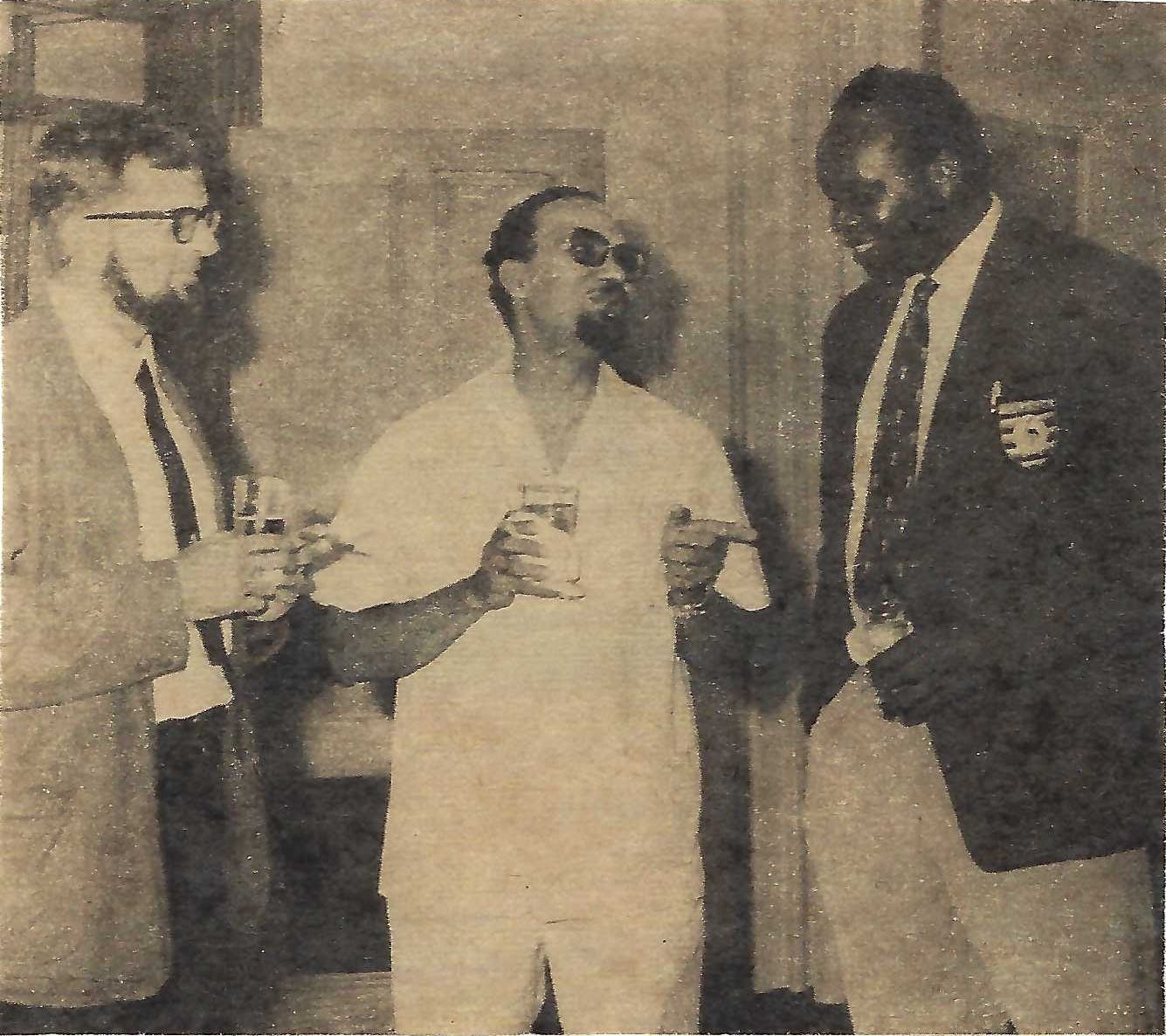

My father, Robert Siedle, left, at Russian Embassy cocktail party talking Israeli ambassador and then-General Idi Amin, right shortly before his disappearance.

My father’s disappearance alerted the world for the first time—as it was immediately reported in Newsweek Magazine—that Idi Amin was brutal—a murderer who would go on to kill an estimated 500,000 of his own people.

The child of a single parent, I had to return to the U.S. and live with relatives I barely knew.

Since he had “disappeared” and was “presumed” dead but his body had not been found, his estate could not be probated, his life insurance benefits would not be paid, and even Social Security Survivor Benefits were unavailable. In short, I was not only orphaned but penniless.

A year after his disappearance, a Ugandan Commission of Inquiry concluded my father had been captured by Amin, tortured and murdered because of his intelligence work.

And, although his body was never found, his estate was able to be probated; his life insurance benefits came through, as did Social Security Survivor benefits.

Through diplomatic channels, the Ugandan Government offered an ex gratia settlement—without admitting responsibility for the murder—and paid reparations to me.

As a result of my father’s work, I was introduced to aging and elder care issues at a very young age. Further, as a result of his murder, I experienced first-hand the value of America’s Social Security system and the benefits it provides, not only to elders in retirement but to their survivors, children and the disabled in critical need.

I also learned early in life to be tenacious in protecting what’s most important, such as health, family and, yes, wealth.

The first forensic investigation of my lifetime—into the disappearance of my father—was not completed until decades later in 1997 when I returned to Uganda and, with the assistance of the American intelligence community and Ugandan military, I sat face-to-face with my father’s murderer at Luzira Maximum Security Prison. Guided by his murderers, I dug for, but was unable to find my father’s remains.

However, I did find the answers I needed about how and when he died, as well as the satisfaction of knowing I had done all I could.

Now, I’d like to talk about my forensic investigations into 401k plans which led me to write nearly 20 years ago: “The great 401k experiment of the past 50 years has failed generations of America’s workers” and “Today there is broad consensus 401ks have not, and cannot, provide meaningful retirement security.”

In 2006, I was retained as a consulting expert in connection with 12 high-profile class action lawsuits filed the same day—September 11th—against many of America’s largest 401k plans, including corporations such as Lockheed Martin, Kraft, Wal-Mart, Caterpillar, Boeing, Northup Grumman, General Dynamics, John Deere, Bechtel, ABB, and Edison.

These were the very first cases to challenge the structure and management of 401ks.

And the findings in these cases were surprising—even to me. I wrote about what I uncovered in my investigations in dozens of articles in Forbes and published an extensive research paper, Secrets of the 401k industry: How Employers and Mutual fund Advisers Prospered as Workers’ Dreams of Retirement Security Evaporated. My paper documented the unsavory industry practices and regulatory failures that played a significant role in creating the defined contribution retirement crisis the nation faces today. The demise of 401ks was no accident and, indeed, was predictable, I wrote.

My research found that 80% of employers believed 401ks were effective in recruiting employees to come work for them but only 13% of employers believed that the 401k plans they offered would provide retirement security for their workers.

In other words, employers understood that offering plans that purported to provide for workers’ retirement security was helpful in building their businesses. However, employers privately acknowledged that these plans were not sufficient to provide for retirement. On the other hand, employers believed that guaranteed retirement income, such as a traditional pension plan, would be far more costly to provide.

So, I wrote: “Do employers tell their workers there really is no retirement security provided if they stay in their jobs—and thereby risk losing employees to competitors? Or do employers maintain the charade that they offer retirement security? Has any employer ever acknowledged to workers it is virtually inconceivable that the defined contribution plan he offers will provide sufficient retirement income?”

I ask you: Have you ever heard an employer admit there is no way workers will ever be able to retire on their 401k savings? I have never seen such a disclosure.

Two weeks ago, I worte an article entitled, Alaska State Workers Hoodwinked Into Believing 401(k)-Style Retirement Plan Was As Good As A Pension, I wrote about my experience as an expert retained to speak on the behalf of City of Atlanta police about a proposal by the city to force workers into a 401k-type plan.

I began my comments to the City Council saying, “We are on the precipice of the greatest retirement crisis in the history of the world.”

“In the decades to come, we will witness tens of millions of elderly Americans slipping into poverty. Too frail to work, too poor to retire will become the “new normal” for elderly Americans.

“If you don’t believe me,” I said, “look at who’s bagging your groceries. It used to be high school kids. Now it’s men and women in their 70s.”

I explained to the City Council that 401(k) defined contribution plans are largely to blame for this foreseeable tragedy and forcing public employees into 401(k)s would only ensure greater misery.

I said, “401(k)s cannot and will not provide meaningful retirement security for the overwhelming number of America’s workers and certainly not the public employees of the City of Atlanta.”

Notice that I did not refer to 401(k)s as “retirement plans” in my comments. That was intentional.

401(k)s were not meant to be retirement plans.

Let me say that again: 401ks were never intended to provide retirement security.

They were initially envisioned as a way for management-level people to put aside extra retirement money—cash in addition to their pensions—like 457 deferred compensation plans for government employees that rely primarily upon pensions for their retirement security.

In the 1980s the 401(k) was embraced by big corporations as a replacement for costly pension funds. Suddenly, large companies were able to transfer the burden of funding employees’ retirement to the employees themselves. Virtually all the major private employers jumped on the bandwagon.

The surreal vision of turning rank-and-file workers into astute portfolio managers, each responsible for successfully directing his own investments, took hold.

Unfortunately, things didn't quite work out as well—for workers—as the employers and financial services companies promised. Since the initial class action lawsuits I was involved with in 2006, virtually all of the largest employers in the world have been sued regarding their 401ks.

Over a decade ago—way back in 2010—84% of Americans surveyed said it was time for new, improved workplace retirement plans. 84% -- that’s a staggering dissatisfaction rate.

As I've said in my Forbes articles, 401ks are the biggest investment fraud ever perpetrated upon America’s workers. I believe it ought to be a crime to call these plans “retirement” plans.

Call them supplemental savings plans or “rainy day” accounts but don’t call them retirement plans and mislead workers to believe that 401ks will provide for their retirement security. They won’t!

Today, with a median 401(k) balance for 65 year olds of $62,000, the decades many elders will spend in so-called “retirement” will be grim.

I told the Atlanta City Council, "So if you do vote to force your city’s public employees into a 401k-type system, at least be honest about it and admit from the get-go that this is no retirement plan.”

In closing, it was no secret in 2006—and it is abundantly clear today—that 401k-type plans do not provide anything near the level of retirement security as pensions.

I feel nothing but compassion for Alaskan state workers who were forced to unwittingly sacrifice their retirement security 17 years ago.

The retirement crisis Alaskan state workers are facing today was foreseeable and, indeed, was foreseen.

My recommendation to you is that a well-managed pension should be established immediately for state workers going forward. But that’s not enough. Workers who were forced into the 401k-type scheme 17 years ago are deserving of compensation that will ensure comparable levels of retirement security. They should not be left behind.

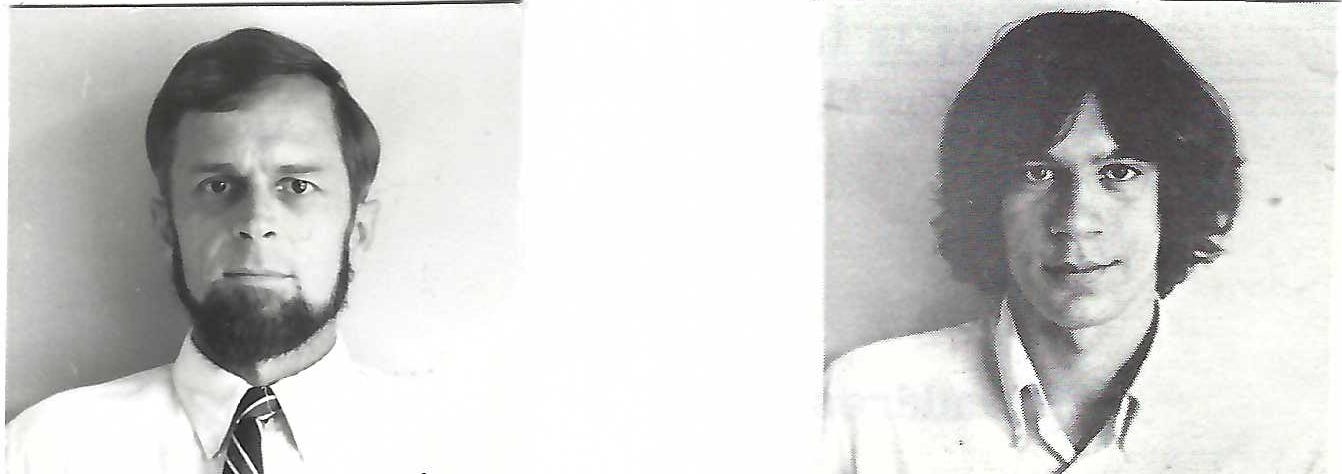

Robert Siedle, father and Edward Siedle, Uganda, East Africa 1971

As I learned in Africa over 50 years ago, you must protect the health and wealth—the lives—of those who are most important to you. I urge you to act to protect the retirement security of Alaska state workers.

"You advocate a "well-managed pension," but can you name one at the state level?"

No, my friend, I cannot. As I explain in Who Stole My Pension?, gross malpractice generally practiced prevails at all public pensions at this time. I will soon post the findings of my forensic investigations of three state pensions--Rhode Island, North Carolina and Ohio--all horribly managed.

"DC isn't inherently less efficient than DB." You're right about this too. The problem with 401ks used to be they paid high retail mutual fund expenses--which were far higher than fees on traditional separate accounts in pensions. But now pensions are in alternative investments that have far greater fees than even retail mutual funds.

DC isn't inherently less efficient than DB. In both, you're investing in mostly the same markets during working years for payout in retirement. DC is much more transparent as to investments and fees. And it is less transparent than DB in terms of benefits that can be provided, and transitioning from DB to DC makes it easy to disguise a benefit cut. But why wouldn't the reasons that have influenced transition to DC in the private sector, where costs are more accurately measured, also apply to the public sector? You advocate a "well-managed pension," but can you name one at the state level? The incentives of all players are aligned toward mismanagement (and you have profited from exposing the results, right?).