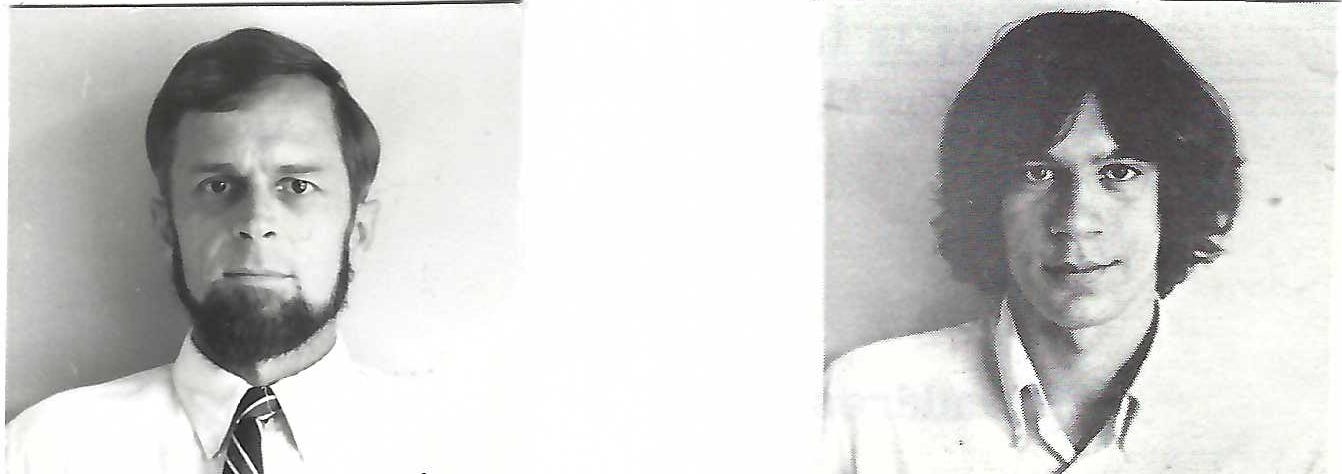

A Teenager Who Became Focused on Pensions and Retirement Plans

In the 1960s, my father foresaw the American elder care and retirement crisis we are struggling with today. Through his work, I was introduced to aging and elder care issues at a very young age.

From the opening chapter of Who Stole My Pension? How You Can Stop the Looting:

Even as a teenager, I was thinking about aging and retirement issues.

That unlikely statement surely requires an explanation.

I spent my teenage years in Uganda, East Africa with my father until one day in July, 1971 he failed to return from a journey—a safari, as we’d say in Swahili—to a remote part of the country.

He and I had celebrated my 17th birthday a few days before he disappeared.

My father was an American professor teaching at Uganda’s Makerere University and conducting field research into care of the aged—the elderly—in African traditional societies.

Why did he choose to study how Africans took care of their elderly?

Because in the mid-1960s, he realized that America’s population demographics—the massive Baby Boom generation—meant that in the decades to come – as 80 million hippies got older—our nation would have to care for them.

For the first time in history, this young nation—a nation which celebrated youth—would have to deal with an invasion of elders.

And America, he knew, was not prepared.

You could say my father foresaw the American elder care and retirement crisis we are struggling with today.

You could say my father foresaw the American elder care and retirement crisis we are struggling with today.

Perhaps how African societies traditionally cared for their elders might provide answers, he thought.

My father traveled extensively throughout the remote parts of Uganda—which we used to call “the bush”—meeting with missionaries and others who cared for elderly, who could not care for themselves. Through his research and travels he developed a wide network—reliable contacts who kept him informed as to happenings in the bush.

Years later, I learned he used the intelligence network he developed to also provide information to American intelligence.

In 1971, when he disappeared in the garrison town of Mbarara, he was investigating rumors that Idi Amin, the new President of Uganda, had killed hundreds of his own army soldiers stationed at the garrison—without firing a single bullet.

My father’s disappearance alerted the world for the first time—it was immediately reported in Newsweek Magazine—that Idi Amin was brutal—a murderer who would go on to kill an estimated 500,000 of his own people.

The child of a single parent, I had to return to the US and live with relatives who I barely knew.

Since he had “disappeared” and was “presumed” dead but his body had not been found, his estate could not be probated, his life insurance benefits would not be paid, even Social Security Survivor Benefits were unavailable. In short, I was not only orphaned but penniless.

Worse still, since, in Africa, my initial attempts at home schooling soon turned to no-schooling—I had never gone to 10, 11 or 12 grade.

Don’t get me wrong—I had learned a lot through reading late at night in my bedroom and helping students with their projects at the African university. But there was no obvious place for me in the traditional American educational system.

The grim reality was that, absent a miracle, I would have to spend the next three years of my life completing high school.

Thankfully, a high school guidance counselor knew of an experimental “early college” called Simon’s Rock in the Berkshire Mountains of Massachusetts—a college that accepted high school aged students.

A helping hand.

A girlfriend drove me to visit the school—since I had only a learner’s permit at the time.

Another helping hand.

This most “unconventional of students” was accepted by this remarkably innovative school and given a full scholarship for my first year.

A path forward—a way out of a hopeless situation—had emerged. I never graduated from high school—never got a high school diploma—but I was accepted as a sophomore in college!

By the end of my first year at Simon’s Rock, things had changed for me.

A Ugandan Commission of Inquiry had concluded my father had been captured by Amin, tortured and murdered, because of his intelligence work.

And, although his body was never found, his estate was able to be probated; his life insurance benefits came through, as did Social Security Survivor benefits.

Through diplomatic channels, the Ugandan Government offered an ex gratia settlement—without admitting responsibility for the murder—and paid reparations.

While I was excited to be a member of the trailblazing first class to receive a Bachelor of Arts degree early from the school—I never graduated from Simon’s Rock.

As you can possibly imagine, once the immediate crisis of my father’s disappearance and murder passed, completing my college education was not an immediate priority. However, after a two year break, I graduated at the top of my class from another college and then law school.

Finally, in May 2018—46 years after I went to Simon’s Rock—I was awarded an Honorary Bachelor of Arts degree from the school that meant the most to me.

In summary, through my father’s work, I was introduced to aging and elder care issues at a very young age. Further, as a result of his murder, I experienced first-hand the value of America’s Social Security system and the benefits it provides, not only to elders in retirement but to their survivors, children and the disabled in critical need.

Through my father’s work, I was introduced to aging and elder care issues at a very young age. Further, as a result of his murder, I experienced first-hand the value of America’s Social Security system and the benefits it provides, not only to elders in retirement but to their survivors, children and the disabled in critical need.

I also learned early in my life to be tenacious in protecting what is most in life, such as health, family and, yes, wealth. The first forensic investigation of my lifetime—into the disappearance of my father—was not completed until decades later in 1997 when I returned to Uganda and, with the assistance of the American intelligence community and Ugandan military, I sat face-to-face with my father’s murderer at Luzira Maximum Prison. My investigation did not bring my father back. Guided by his murderers I dug for, but was unable to recover, my father’s body. But I did find the answers I desperately needed about how and when he died, as well as the satisfaction of knowing I had done all I could. The story of my return to Uganda in 1997 to investigate my father’s murder is told in the recent book, Buried Beneath a Tree In Africa.

Over the past 40 years, as a former U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission lawyer and corporate whistleblower securing the largest government awards in history, I have pioneered the field of forensic investigations of the money management business. These days when I’m asked to explain what I do for a living—in terms anyone can understand—I say:

“It’s like the television show CSI: Miami. Each episode of the show typically opens with the discovery of a dead body and the job of the forensic investigators is to figure out whether the death was due to natural causes or foul-play. In my work, the “death” I’m investigating is a dead, or seriously sick, pension or investment. The question is, did the pension fail due to natural causes (such as unforeseen stock market declines), or was there foul-play? The wrongdoing I look for is undisclosed conflicts of interest, hidden and excessive fees or outright violations of law. More often than the public or even victims ever imagine, the injury or damage is caused by wrongdoing– unethical, self-dealing Wall Street investment firms who drain client accounts for their own benefit.

It’s a wealth transfer game these guys play: your wealth gets transferred to them.”

To date, I’ve undertaken deep-dive forensic investigations into well over $1 trillion in retirement plans and uncovered hundreds of billions successfully stolen without a gun or whimper from the victims, including pensions set aside for government workers, as well as corporate pensions sponsored by some of the world’s largest employers.

I know what makes even the biggest, supposedly well-managed pensions and other retirement plans falter and fail. And I know what you can do – what you need to do—to keep your pension from being stolen.

You—all of us—deserve a safe and secure retirement. This book will hopefully bring you one step closer to that goal.

To order Who Stole My Pension? click here.

Edward, this very touching personal story deserves to be told everywhere. Moreover, the parallels that are happening right now (and have been ongoing for at least a few decades) with the health benefits industry are almost identical. You and I should write the second edition of your book, detailing how the American healthcare industrial complex stole an otherwise great opportunity to retire and thrive. Instead, many Americans who want to retire cannot do so because healthcare systems have taken everything they could and then some from every outlet they could access.

Why did you hook up with a fraudster yourself though ?

AKA Kiyosaki ?

I'm not perfect either

I'm just curious

Thanks in advance